Energy dispute over Rockies riches

A trove of oil shale may be a boon. But the science to extract fuel is imperfect, and locals worry about their water supplies, which ultimately feed Southern California reservoirs.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, December 28, 2008

Julie Cart

Reporting from Salt Lake City — A titanic battle between the West’s two traditional power brokers — Big Oil and Big Water — has begun.

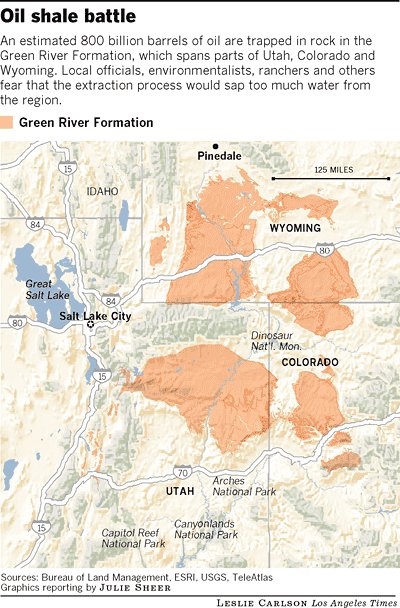

At stake is one of the largest oil reserves in the world, a vast cache trapped beneath the Rocky Mountains containing an estimated 800 billion barrels — about three times the reserves of Saudi Arabia.

At stake is one of the largest oil reserves in the world, a vast cache trapped beneath the Rocky Mountains containing an estimated 800 billion barrels — about three times the reserves of Saudi Arabia.

Extracting oil from rocky seams of underground shale is not only expensive, but also requires massive amounts of water, a precious resource crucial to continued development in the nation’s fastest-growing region.

The conflict between oil and water interests has now come to a head. On Oct. 31, Congress allowed a moratorium on oil shale leasing to expire. That paved the way for the Bush administration to finalize leasing rules last month that opened 2 million acres of federal land to exploration.

Oil companies say that at a time of increasing foreign oil dependence, it would be unconscionable to forgo exploiting oil shale’s potential.

“Considering the magnitude of this resource — it is so huge relative to other hydrocarbon resources around the world — it merits taking a look at trying any method we can, safely and responsibly, to get at it,” said Tracy C. Boyd, communications and sustainability manager for Shell Oil Co.

Oil shale companies acknowledge that the technology required to superheat shale to extract oil is unproven. They also acknowledge that they are uncertain how much water would be needed in the process, although some experts calculate it would take 10 barrels of water to get one barrel of oil from shale.

That water-to-oil equation has inflamed officials in the upper Rockies, who are raising the alarm about the cumulative effect of energy projects on the region’s water supplies, which ultimately feed Southern California reservoirs via the Colorado River.

“There are estimates that oil shale could use all of the remaining water in upper Colorado River Basin,” said Susan Daggett, a commissioner on the Denver Water Board. “That essentially pits oil shale against people’s needs.”

Even with the precipitous drop in oil prices and the staggering start-up costs and risks associated with oil shale exploration, oil companies are rushing ahead.

“As long as we continue to be a nation that is hooked on liquid fuel,” said Boyd, “we need to look at anything we can do to tap the sources of energy in this country.”

Prospectors have known about the oil shale deposits in the Rockies for more than a century, but the technology to extract it has remained imperfect, expensive and polluting.

A variety of experimental methods have been developed. Although details are closely held, the broad outlines are similar.

Shell has the most mature technology, which it has been experimenting with at its Mahogany test site, near Rifle, Colo. Tucked into a rolling landscape of empty range land, the company has sunk heaters half a mile into oil shale seams and subjected the rock to 700-degree temperatures. Over weeks or even months, a liquid known as kerogen is produced, which can be refined into diesel and jet fuel.

To prevent the brewing hydrocarbons from spoiling groundwater, the heated rock core is surrounded by 20-to-30-foot-thick impermeable ice walls, frozen by electric refrigeration units.

Other companies’ methods are more akin to open pit mining, in which millions of tons of rock are excavated and then fed into a massive above-ground cooker.

All of the processes require prodigious amounts of water, either for the electrical plants needed for heating and freezing or for the web of industrial facilities needed to extract the oil.

But for all the years of research into oil shale extraction, there is little hard information on exactly how much water would be drained from the region.

In its recent environmental review of proposed oil shale projects, the federal Bureau of Land Management, which oversees energy leasing on public lands, was unable to estimate the industry’s region-wide water use.

Mike Vanden Berg, the Utah Geological Survey’s principal researcher for oil shale projects, said, “I still don’t know how much water is used. . . . No one does.”

Meanwhile, already- parched Western states bracing for more growth are completing water supply inventories. A Colorado study projected that by 2050, with the state’s oil shale operations at full capacity, the industry will require 14 times more power than currently generated by the state’s largest power plant.

The study’s sobering bottom line is that meeting oil shale’s energy demands could require more water than Colorado is entitled to under an interstate compact.

“Can groundwater be protected?” asked Harris Sherman, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. “Areas where this technology will be used are all tributaries for the headwaters for all of the seven Colorado Basin states.”

Despite the objections, oil shale development has been pushed forward by a series of recent actions. In an effort to encourage the fledgling industry, officials said, new regulations allow oil shale operators to pay unusually low royalty rates. The system calls for producers to pay 5% for the first five years, increasing 1% each year until reaching 12.5%, the standard federal oil and gas royalty rate.

In recent weeks, the industry was included in the $700-billion government bailout package with investment and tax incentives to help oil shale producers build refineries and other expensive infrastructure.

Though the region’s elected officials support efforts to discover new sources of domestic oil, they say that with so many unanswered water questions, public land managers should be slowing the pace of development, not speeding it up.

The governors of Colorado and Wyoming have expressed concerns about the venture’s effect on water in their states.

Not so, Utah. The state contains the least-rich shale deposit but is the most enthusiastic booster of the unconventional oil source. Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. recently declared Utah “open for business as it relates to oil shale.”

The renewed push for oil shale development comes at a time when conventional energy companies are being blamed for squandering and fouling water across the West.

Wyoming and Montana are squabbling over water quality concerns about coal-bed methane drilling. Colorado and New Mexico towns have discovered benzene and other dangerous chemicals in their wells, with energy projects the suspected culprits.

Ranchers in the region say their crops and livestock suffer as oil and gas production drains underground aquifers. Sportsmen complain that rivers and streams are being compromised by the energy industry.

The Environmental Protection Agency, in official comments to the Bureau of Land Management, expressed concerns about the possibility that oil shale production would deposit “salts, selenium, arsenic, and polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in groundwater.”

Craig Thompson found many of the same compounds when he studied groundwater pollution from an abandoned oil shale project in western Wyoming that began during the last oil shale boom, in the 1970s. Despite 30 years of cleanup efforts, he said, the aquifer is still not free of chemicals.

“Development of oil shale is a groundwater nightmare,” said Thompson, a chemist. “Oil shale serves as the floor for the aquifer. When you heat up the aquifer, it dissolves nasty stuff like fluoride and arsenic and selenium and cyanide . . . the list goes on.”

For now, with the support of Congress and the Bush administration, oil companies appear to have the upper hand.

That might change with President-elect Barack Obama’s selection this month of Colorado Sen. Ken Salazar, a former water lawyer, to head the Department of Interior.

Salazar, a Democrat, has criticized the breakneck speed at which oil shale efforts are advancing.

“Over and over again the administration has admitted that it has no idea how much of Colorado’s water supply would be required to develop oil shale on a commercial scale, no idea where the power would come from and no idea whether the technology is even viable,” Salazar said last month.

But as long as the demand for fuel remains high, the dream of squeezing oil from rock will probably persist.

“Oil shale is the last refuge of the hydrocarbon pioneers,” Thompson said. “It’s always been that last refuge because it’s such a poor excuse for a fuel. Here’s a commodity that’s been developing for 100 years, and we still don’t know anything about it.”

0 Comments