Why the Colorado river is drying up – and what we can do about it

The Colorado river is the lifeblood of the US Southwest, but today it is drastically depleted due to overuse, megadrought and climate change. Here’s how to rescue it.

Source of this article, New Scientist, November 22, 2023

“The river was nowhere and everywhere,” wrote naturalist Aldo Leopold of the Colorado river delta, the region where waters originating in the Rocky Mountains meander into the Gulf of California in Mexico. Having explored the area by canoe in 1922, Leopold described the vast wetlands as a swirl of “a hundred green lagoons”, “awesome jungles” and “lovely groves”.

A century later, Leopold wouldn’t recognise the delta. The lagoons have mostly turned to dust as a series of giant dams prevented the river from reaching the sea reliably for the past few decades. “The drying up of the river is certainly an indication that something wrong is happening,” says Karl Flessa, a hydrologist at the University of Arizona.

Upstream, the Colorado has been drastically depleted. That is partly down to the fact that people are taking too much water out of the river basin and partly down to a megadrought, exacerbated by climate change, which means the region the Colorado flows through is the driest it has been in 1200 years.

Now, the river’s plight has reached crisis point. In 2021, the US federal government for the first time declared a water shortage at Lake Mead, a reservoir created by damming the Colorado, triggering cuts in supply to farmers. Some researchers are even voicing concerns that the megadrought might indicate a region undergoing aridification, the gradual change from a wetter to a drier climate, which would put the river in grave peril.

It is hardly surprising, then, that everyone who relies on its water is asking the same question: can we save the Colorado?

Renowned for its dramatic canyons, this iconic river stretches some 2300 kilometres across the western US and, for a long time, northern Mexico. It is known as the Nile of North America because as well as being a scenic and ecological wonder, it is a vital resource for more than 40 million people across seven US states, plus 29 Native American tribes that have rights to some of the water. It supplies US cities including Phoenix and Las Vegas and countless farms, and it is dammed to create two major reservoirs – Lake Mead in Nevada and Arizona, and Lake Powell in Utah and Arizona – that produce crucial hydropower for the region.

The way we use this natural resource can be traced back to 1922, the year Leopold canoed the delta, when the Law of the River was born. This is the name given to the collection of interstate agreements, US federal laws, court decisions, regulations and an international treaty that govern the use of the Colorado waters. It started with the Colorado River Compact, which divvied up the river system, with its myriad tributaries, into two regions known as the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin.

Under the compact, the states that draw water from the Upper Basin – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – agreed to taking a share that left enough water to filter down to the Lower Basin states, which include Arizona, California and Nevada. Each basin could draw roughly the same amount of water, about 7.5 million acre-feet – an acre-foot being the volume of water that would cover an acre to a depth of 1 foot – which is the equivalent to 9 billion cubic metres. The states were to decide how to split that up among themselves. The compact was the first time more than three states had negotiated water rights from the same river, and it enabled massive growth in the south-western US.

But even back then, alarm bells were ringing. The amount of water allotted for use in the compact was determined using records from the early 20th century, an exceptionally wet period known as the North American Pluvial. In 1928, William Sibert, chair of the Colorado River Board, warned that this meant major droughts would be likely in future. “It is quite probable that the compact attempts to apportion more water than the actual average undepleted flow of the river,” he wrote.

The number of people living in the region has risen sharply since then, so the volume of water tapped has increased too. These days, agriculture consumes 70 to 80 per cent of the river basin’s water every year, with thirsty cities drawing about 15 per cent. “Now we’re facing the consequences,” says Flessa.

The pressure on the river system has also been ratcheted up by a megadrought that has gripped the western US for the past 22 years, leaving it parched. That has led to a severe drop in the water available, with the average annual flows into Lake Mead and Lake Powell nearly 20 per cent below the average flows into those reservoirs during the 20th century.

In the Colorado’s Upper Basin, up to half the decline in water flow has been attributed to climate change. There has been less rain but it is more complicated than that. Warmer temperatures mean the snowpack in the region’s mountains melts more quickly than it used to, cutting down on one of nature’s best ways to store water without evaporation. Meanwhile, warmer air pulls more moisture out of the soil so more of the snowpack melt is soaked up rather than going into the river.

Climate models suggest that if warming continues, the river’s flow could be reduced by 30 per cent by 2050 and 55 per cent by the end of the century. With a hotter future, the Colorado could see the decline of an important source of replenishment known as baseflow -moisture that enters groundwater stores and then moves into the river as it seeps out into streams or springs that feed it. “Baseflow contributes over 50 per cent of the water in the upper Colorado river basin,” says Olivia Miller, a hydrologist with the US Geological Survey.

She and her colleagues modelled how the river might respond to climate change in the Upper Basin. They found that under a warm and wet scenario, baseflow would initially increase in the 2030s, but ultimately decline by 3 per cent from today’s levels by the 2080s. Under a hot, dry climate, baseflow was predicted to decline by up to 23 per cent in the 2030s and reach a 29 per cent decline by the 2050s.

Historic lows

“I think about it like a financial budget,” says Miller – and when it comes to the Colorado, it is clear that we are living beyond our means. As Kevin Wheeler at the University of Oxford and his colleagues showed in an analysis published in 2021, since 2000, the average natural flow in the Colorado has dropped to 15.1 billion cubic metres per year – some way short of the 20.3 billion cubic metres now allocated for use under the Law of the River.

Today, the two major reservoirs on the river are at historic lows. If the water levels dip much lower, the Colorado’s northernmost reservoir won’t have enough in the tank to both fill Lake Mead downstream and generate any hydropower, which would have devastating effects on the electricity grid in the western US.

That doesn’t mean the river will die: Miller says it would be hard to imagine it drying up completely. “For that to happen, we would essentially need no precipitation,” she says. So it is unlikely the entire 2300-kilometre stretch of river will disappear in the coming decades. But portions of it could slow to a trickle and if aridification does take hold, this could be the start of the river’s demise. “No one was expecting the drought to last this long,” says Wheeler. “There is a significant possibility this is driven by aridification.”

What is clear is that the drying of the Colorado has got to the point where urgent action is required. “The system is at a breaking point right now,” says Wheeler.

What we should do depends on what you are trying to achieve. Few people are suggesting we can restore the river to its natural state, because everyone recognises its importance to the lives and livelihoods of millions of people. Even so, Flessa and his colleagues are among those attempting to revive the ecological health of the delta and connect the river to the sea again, by periodically releasing water from dams in so called “pulse flows”.

In 2014, the largest of these left the gates of the Morales dam on the Arizona-Mexico border, releasing 130 million cubic metres of water towards the Gulf of California. Eight weeks later, aerial surveys showed that the water had spread through the parched land and trickled towards the ocean. The Colorado river had connected to the sea for the first time in nearly 20 years.

In the time since, several smaller pulse flows have irrigated restoration sites in the delta in northern Mexico. It remains to be seen what long-terms benefits that will bring to people there who have suffered as fishing opportunities dried up. But willow and cottonwood trees are coming back. “These are classic riparian vegetation in the arid west,” says Flessa. “With a lot of care and a little bit of water, these riparian forests have grown 20-foot-tall trees in eight years, and they provide habitats for resident and migratory birds. And beavers are back!”

For the most part, however, scientists are concerned with safeguarding the river’s future to ensure that it can continue to supply water for the millions of people who depend on it.

One option is to reduce evaporation from water sitting in the big reservoirs. The Colorado basin loses an average of about 2.5 billion cubic metres, or roughly 12 per cent of its annual water supply, to evaporation each year. Estimates suggest Lake Powell sees annual evaporative losses of 470 million cubic metres – that is more than the state of Nevada takes from the river system. Lake Mead sees around twice that much evaporation.

There have been some attempts at reducing evaporation. Shading reservoirs with floating plastic spheres that reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the water has been tried in some places, for instance. But the truth is that they haven’t been very successful, says David Freyberg, an environmental engineer at Stanford University in California. “It’s very hard to suppress [evaporation]. A few smaller reservoirs in southern California have tried floating a zillion little black balls on the surface, but the challenge is that it’s very hard to find something that wind doesn’t disrupt,” he says.

The other big idea is to redirect flood waters to replenish parched aquifers. One of the anticipated impacts of our changing climate is that river flows will become more variable, with higher flood peaks in wet years and longer dry periods in dryer years. “If we could somehow capture those higher peak flows and put them into the ground where they are stored without evaporation, then we might be able to, in a sense, live with a changing climate and better manage the resources,” says Freyberg.

He is among those backing a proposal for California known as Flood-MAR, the latter half of which stands for “managed aquifer recharge”. He argues that it could help take advantage of the massive dumps of rain that do still hit the western US sometimes despite the drought. What’s more, underground storage also avoids some of the ecologically disruptive impacts of dams and reservoirs. “There’s way more volume available in the subsurface to store water, all those pore spaces in the rock down there,” says Freyberg.

Cutbacks coming

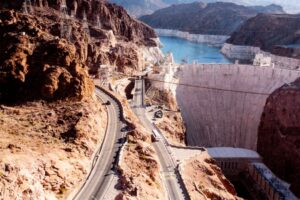

Perhaps the most drastic proposal to conserve the Colorado’s stocks is a plan called Fill Mead First, which would consolidate most of the water from both major reservoirs on the river downstream into just one, Lake Mead, which forms behind the Hoover dam in Nevada. The Glen Canyon Institute (GCI), a conservation group that aims to restore the Colorado through Glen Canyon, where the other big reservoir, Lake Powell, is located, commissioned a study in 2013 to assess the impact of letting Lake Powell empty out. Under this proposal, the dam that creates the lake would be opened to lower its levels to the minimum at which hydropower can be produced before tunnels would be built around the dam to eventually allow the river to flow freely again.

The idea is not only to restore the ecology of Glen Canyon, but also to reduce evaporation and losses to ground water seepage, which is a problem because of the canyon’s porous sandstone walls. The GCI analysis suggested that this could save 370 million cubic metres of water each year, though a separate analysis conducted at Utah State University found that it would be closer to 62 million cubic metres.

Others aren’t so enthusiastic. Lake Powell is part of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, which draws millions of visitors who spent $332 million in the area last year. It not only supplies power, but jobs too, so any proposal to cut off that tap is a tough sell. “The question of which reservoir the water sits in is mainly a political one,” says Wheeler.

The truth is that when it comes to restoring the Colorado’s water supply, there is no silver bullet. With no end in sight for the drought gripping the US west, it is impossible to avoid the reality that we have to start pulling less water out of the river. “We can’t increase supply,” says Wheeler. “So the only lever we really have is demand management.”

In that vein, Nevada enacted a law to ban “non-functional turf” by the end of 2026. This is grass that nearly nobody uses, such as lawn in business parks and central strips that separate two sides of a road, and yet it requires a lot of water. Nevada’s ban is the first such law in the US to prohibit grass in certain areas, though California has also recently banned the watering of non-functional grass.

Wider action is also under way. In October, the US Department of the Interior announced that it will pay farmers, cities and Native American tribes to voluntarily cut back on the amount of water they take out of the river. The programme will be funded with a portion of the $4 billion appointed for drought mitigation under the landmark Inflation Reduction Act passed earlier this year.

Wheeler also suggested that farmers could be subsidised by the government to grow higher-value crops with the water they do use, shifting from alfalfa used for animal feed to other plants. Freyberg also says that crop selection may need to change: “My guess is that we’re going to see some fairly dramatic changes in western agriculture. I don’t see how we can avoid that, to be honest.” It isn’t yet clear what those changes will be, but cereals, canola, chickpeas, and leafy greens are among the crops being proposed as a way to keep land productive while reducing irrigation needs.

The time to plan is now. A number of agreements that govern the use of the Colorado are set to expire in 2026, and must be updated with a dryer climate in mind. “It’s often been debated whether it’s time to renegotiate the compact,” says Wheeler. “Most of the states’ representatives have said this would open up a can of worms that would be too difficult to contain. However, if we are not going to fundamentally change or replace the compact, we may have to bend the hell out of it to make it work for a new era moving forward.”

If not, Leopold’s maxim about the lush river delta may get turned on its head. If the river is allowed to be used unchecked, it will be everywhere and nowhere.

0 Comments