Gray wolf likes California but is unlikely to find a mate here

The young male from Oregon has remained in the Golden State since spring and covered about 3,000 miles. He’s also shown exceptional homing abilities.

Source of this article: The Los Angeles Times, January 2, 2013

Like many out-of-state visitors, the lone gray wolf that trotted across the border from Oregon has taken a liking to California.

photo from a hunter’s trail camera appears to show OR7, the young male wolf that has traveled more than 3,000 miles since leaving his pack in northeastern Oregon.

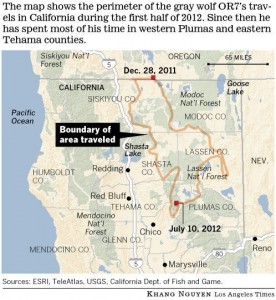

He went back and forth between the two states a handful of times after his initial crossing into Siskiyou County on Dec. 28, 2011. But since spring, the young male has remained in the Golden State, loping across forests and scrublands, up and down mountains and across rural highways in California’s sparsely populated northeast.

The first wild wolf documented in California in nearly 90 years, he has roamed as far south as Tehama County — about halfway between the border and Sacramento — searching for other wolves, and a mate.

“I guess he’s being the Lewis and Clark of wolves in California,” said wolf advocate Amaroq Weiss.

State and federal biologists are using a tracking collar to follow OR7 — his official designation — and they’re impressed. Not only has he traveled more than 3,000 miles since leaving his pack in northeastern Oregon, he’s demonstrated exceptional homing abilities.

“He can find the same locations [after] weeks, sometimes a couple of months, coming back from a completely different direction,” said Karen Kovacs, wildlife program manager for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Since summer, OR7 has spent most of his time in western Plumas and eastern Tehama counties on a mix of public and private lands, with some jaunts into neighboring Butte County. He seems to dine mostly on mule deer, following their seasonal migrations from mountains to lower elevations.

Since summer, OR7 has spent most of his time in western Plumas and eastern Tehama counties on a mix of public and private lands, with some jaunts into neighboring Butte County. He seems to dine mostly on mule deer, following their seasonal migrations from mountains to lower elevations.

Fortunately for him, he has avoided people and livestock. The wolf was accused of killing a cow and her calf and some other livestock, but Kovacs said investigations found no evidence that OR7 was the culprit. The cow died giving birth to the calf, which was either born dead or died soon after birth and was then eaten by coyotes.

There have been a number of reported sightings of the 3-1/2 -year-old wolf, but only a few have been confirmed. One was in a state wildlife area in November, when a man hunting with his daughter saw a group of deer emerge from a woodland. Behind it was a single deer running from what appeared to be a wolf. The animal broke off the chase, looked in the direction of the hunters and trotted away.

The excited pair reported the sighting, and radio signals placed OR7 in the area. “The timing, the behavior, the location; we’re pretty sure it was OR7,” Kovacs said.

Although he has journeyed much farther from his home pack than is typical, the wolf is doing what young males do, searching for a mate and other wolves with which to form a pack. He returns to areas where he has left his scent, hoping to find signs of other wolves.

It is possible that other gray wolves without radio collars have crossed into the Northern California wilds from Oregon, where there are a number of packs. But biologists have found no evidence of them, and Kovacs said the chances are slim that OR7 will find a mate in California.

But he has found food and remote country and appears to be healthy. “Being an apex predator in a landscape that hasn’t had one for a pretty long time — he’s got it pretty good right now,” said Steve Pedery of Oregon Wild, an environmental advocacy group.

Gray wolves in California are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. After OR7’s arrival, several conservation organizations petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Department to place the species on the state endangered list; and the department is now preparing a report on the matter.

Boards of supervisors in several northern counties oppose a state listing, and ranchers in the rural areas where OR7 is roaming have not exactly rolled out the welcome mat. “Clearly there are some who are wolf lovers and some who are wolf haters,” said Kovacs, who has made wolf presentations at public meetings.

Regardless of whether OR7 stays in California, wildlife biologists expect more wolves to follow. The Fish and Wildlife Department intends to prepare a wolf management plan for the state, and conservationists have formed an alliance to promote wolf recovery on the West Coast.

“It’s a different environment” in the Pacific Coast states than in the interior West, said Weiss, Northern California representative of the California Wolf Center.

Idaho, Montana and Wyoming authorized gray wolf hunts after the northern Rocky Mountain population was removed from the endangered species list. Hundreds of wolves have been shot and trapped in the last couple of years, including the popular alpha female from a Yellowstone National Park pack who wandered outside the park.

OR7 “was smart enough to come here instead of Idaho,” Weiss said. “The Pacific Coast may be the only area in the U.S. where wolves are allowed to survive and thrive.”

0 Comments