Utah fighting the laws of federal land

The state is helping pay for legal challenges to federal jurisdiction, much of it, critics say, without oversight.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2007

Julie Cart

Bill Hughes of Moab drives along the Amasa Back Trail in Kane Creek Canyon near Moab, Utah. The surrounding land is federally owned and some of it is off limits to motorized recreation, but with financial help from the state, Grand County and others in southern Utah are challenging the federal government for jurisdiction.

RECAPTURE CANYON, UTAH — It’s a small gesture of defiance — a narrow metal bridge that allows off-road vehicles illegal access to this archeologically rich canyon. But the modest structure, built by San Juan County officials on U.S. government land, is a symbol of the widespread local resistance to federal authority across much of southern Utah’s magnificent countryside.

Historically, people in the rural West have challenged federal jurisdiction, claiming ownership over rights of way, livestock management and water use. But nowhere is the modern-day defiance more determined, better organized or more well-funded than in Utah, where millions of taxpayer dollars are being spent fighting federal authority, and where the state government is helping to pay the tab, much of it, critics say, without oversight.

Lynell Schalk,a former BLM law enforcement official, crosses an illegal bridge recently installed in Recapture Canyon, near Blanding Utah, that allows off-road vehicle access. (Spencer Weiner / LAT)

For the last decade the Utah Legislature and two state agencies have been funneling money to southern Utah counties to bankroll legal challenges to federal jurisdiction. Most recently, a state representative persuaded the Legislature to provide $100,000 to help finance a lawsuit by ranchers and two counties seeking to expand cattle grazing in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Grand Staircase is one of a dozen parks and monuments that draw tens of millions of visitors to the region every year to take in the spectacular high desert and red-rock canyons that have awed travelers since John Wesley Powell voyaged down the Green and Colorado rivers in 1869.

Settlers, on the other hand, have been famously indifferent to the scenery. “A hell of a place to lose a cow,” is how 19th century homesteader Ebenezer Bryce is said to have described the labyrinthine landscape now known as Bryce Canyon National Park.

“This is a beautiful and unique land,” said Bill Smart, retired editor of Salt Lake City’s Deseret News. “It’s distressing that we can’t all be more appreciative of the values that other people see here. To me it’s very disappointing that our own people can’t see what we have.”

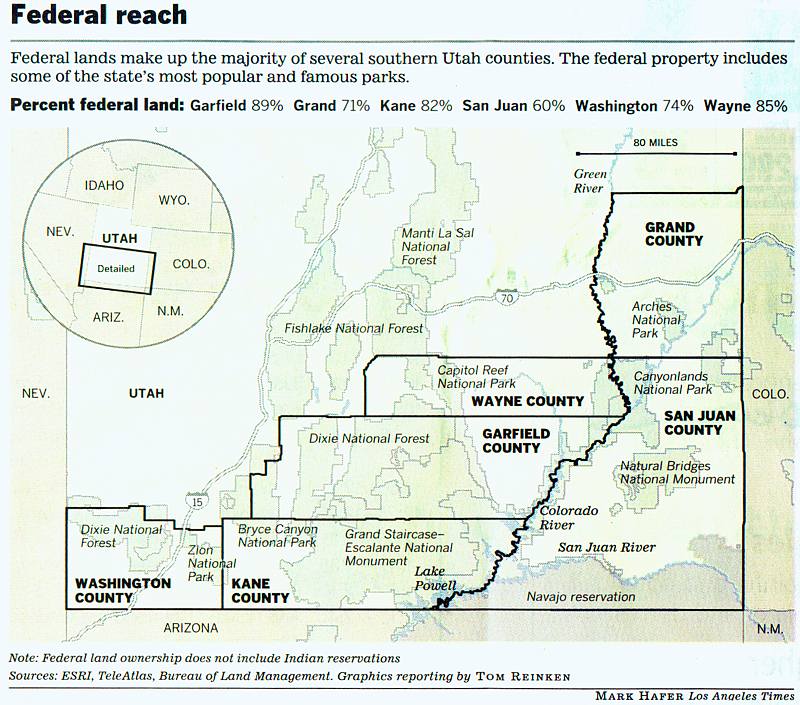

In southern Utah, where the U.S. controls nearly 90% of the land in some counties, many residents feel they are permanent tenants on land their ancestors pioneered. The resentment hardens whenever the Washington, D.C., landlord imposes restrictions on ranching, mining, energy development and motorized recreation.

Schalk checks damage at an ancient Pueblo archeological site in Arch Canyon. Schalk is among a coalition of activists and environmentalists who filed a petition demanding a vehicle ban in Arch Canyon. (Spencer Weiner / LAT)

“Who gets to control the land is the great American story,” said Karl Jacoby, associate professor of history at Brown University. “In part it is about economics, but a lot of it is about identity and who we are as a people.”Officials of one county have written a bill pending in Congress that orders the sale of federal land, with the proceeds given to the county. Other Utah counties have said they will follow suit. And officials from the two counties surrounding Grand Staircase have lobbied in Washington to dramatically reduce the 2-million-acre national monument.

Elected officials have flouted federal authority by bulldozing roads in the Grand Staircase monument and Capitol Reef National Park, and by tearing down signs banning off-road vehicles in Canyonlands National Park. A handful of counties have developed transportation plans that declare roads open that federal land managers have closed.

Selma Sierra, Utah director of the federal Bureau of Land Management, insisted that the agency’s relationship with counties was good. “The BLM manages a substantial amount of land in this state. Yes, those lands belong to everyone in the country, but the decisions we make affect those individuals more so than anywhere else.”

Kent Hawkins of Blanding gives his family a ride on an ATV in Recapture Canyon. The canyon is dotted with fragile archeological sites that are being damaged by motorized recreation, according to a recent assessment by the federal Bureau of Land Management. Like much of the land in southern Utah, the canyon is owned by the federal government which controls access and limits vehicle use. But rural counties are promoting motorized recreation, along with other uses such as mining and livestock grazing. (Spencer Weiner / LAT)

But federal officials say increases in motorized recreation and scarring of the landscape from energy exploration are threatening unique historic and cultural treasures and damaging wildlife habitat.

A recent BLM archeological assessment of 3rd century Anasazi ruins and cliff dwellings in Recapture Canyon found evidence of looting and off-road vehicle damage. According to the assessment, the new, county-built bridge “can be expected to hasten and increase indirect impacts to cultural resources here.”

“It’s quite common in Utah to hear people say, ‘The federal government should give the land back to the state.’ But the state never owned it,” said Daniel McCool, director of the American West Center at the University of Utah.

McCool said rebellious county commissioners no longer represented the demographic of the American West. “There is a new rural resident,” he said. “They didn’t move here to ranch and raise cattle. They moved here for the amenities value of the public lands. That’s what’s driving the economy now. Today, the single largest nongovernmental components of Utah’s economy are tourism and recreation. Mining, grazing and agriculture are about 3% to 4% of the economy.”

According to an economic analysis commissioned by the National Parks Conservation Assn., national parks generate at least $4 for state and local economies for every dollar in the parks’ budgets. Zion National Park, in southwest Utah, had 2.5 million visitors last year and provided nearly $100 million in annual recreational benefits to the surrounding county, the study said.

Grand Staircase was responsible for “substantial” economic growth, higher employment and increased personal income in two surrounding counties, according to a 2004 study by the Sonoran Institute, a nonpartisan research group in Tucson.

Grand and San Juan counties, near Moab, boast that they have thousands of miles of four-wheel-drive routes. Most are old and unmaintained trails that were used for mining or prospecting. Bob Moore of Highland, Utah, powers through a creek crossing on the Kane Creek Canyon four-wheel-drive trail. (Spencer Weiner / LAT)

But Utah Lt. Gov. Gary R. Herbert said in an interview that the state had endured an “erosion of rights.”

“We’re not going to sit back anymore, we’re going to be proactive, we are going to protect our rights,” he said.

State Rep. Mike Noel, a Republican from the southern community of Kanab, said: It gets down to “sovereignty and autonomy. It’s Western independence. We own the water, we have the right to graze, the minerals are still available, and the roads belong to us. By dang, we are not going to give them up.”

Noel is part of a self-styled “cowboy caucus” in the Legislature that has helped direct hundreds of thousands of state dollars to counties bickering with the federal government.

In addition, the Constitutional Defense Council, established to protect state and county interests on federal land, has paid out more than $10 million, much of it to assist southern counties in legal battles against the BLM and the National Park Service.

The 2-year-old Public Lands Policy Coordination Office last year offered each county in Utah $10,000 to fight for rights of way across federal land and is funding a $1-million study on the economic impact of large federal holdings in the state.

Critics say taxpayer money should not be used to fight these legal battles and argue that there is little accounting of how much money is spent by the Constitutional Defense Council and public lands office. A 2004 state legislative audit of the Constitutional Defense Council concluded that it provided inadequate financial detail about its operations and recommended that it issue regular financial statements.

Even one of the guiding lights behind the creation of the Constitutional Defense Council said he couldn’t trace how its money was spent. “There are no records, no agenda, no minutes,” said Mark Walsh, executive director of the Utah-based Western Counties Alliance, who wrote some of the language that established the council. “It’s a little confounding to me that you’ve got millions going into that office, but no one knows how it’s spent or on what projects.”

This month, a federal judge ruled that two southern Utah counties illegally used public funds to pay costs in a grazing lawsuit brought by local ranchers against the BLM.

Bob Keiter, a University of Utah law professor and public lands scholar, suspects Utahans are largely unaware that the state is helping bankroll the counties’ legal fights.

“The question is whether or not the citizens of the state realize the degree to which they are subsidizing litigation that cuts across their interests,” said Keiter, director of the Wallace Stegner Center for Land, Resources and the Environment.

Rural interests continue to dominate the state legislative process in a manner that is out of proportion to their representation, Keiter said.

They also have influence with the Bush administration. In 2003, the administration agreed to withdraw 2.6 million acres in Utah from wilderness protection, and recently the BLM reinstated leases that could lead to extensive coal mining in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

0 Comments