The Santiago Truck Trail in Orange County

Rolling in agony and ecstasy: The path to Shangri-La in the Santa Anas pushes bikes and muscles to the thigh-burning limit.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2005.

By ROY M. WALLACK, Special to The Times

EN ROUTE: The 18-mile Santiago Truck Trail, perfect for bikers, dips and rises into overgrown wilderness before reaching a mountain meadow.

THE Santiago Truck Trail is no longer passable by trucks — or any four-wheel vehicle for that matter. But it’s perfect for hikers and bikers looking for more adventure. Like me. I was tired of the same 90-minute mountain-bike loop every Saturday. A friend of mine, John Kennedy, a maker of sleight of hand devices for professional magicians, had a new trick up his sleeve: “We’re going to Old Camp,” he said, pitching me on an 18-mile thigh-burner not far from our Irvlne homes.

And so began the ride that would not end, a journey into the mythical hunting grounds of the Juaneno Indians, a Shangri-La deep in the bowels of the Santa Ana Mountains.

Snaking up the south-facing edge of the surprisingly stout Santa Anas, which top out at 6,000 feet as they separate Orange and Riverside counties, the Santiago Truck Trail provides striking views of the ocean, the coastal mountains and the nearby neighborhoods of Portola Hills. We pushed off on the eroded double-track at 2 p.m. in brilliant rain-washed sunshine, hungering tor the euphoric mix of respiration, inspiration and isolation that only comes with mountains big enough to lose yourself. Some people spend a lot of money to ride the Rockies. In the O.C., we’ve got plenty of peaks in our own backyard.

After climbing 500 feet in 3.5 miles, I hesitated at the intersection of Vulture Crags Trail, named for the California condors which nested in the nearby cliffs until farmers exterminated them 50 years ago. To mountain bikers, this trail is known by a different name: the Luge, 1.5 miles of steep sycamore- and oak-studded single-track with a distinctly carved rut in the center. It’s an ideal, if frequently bloody, exclamation point to this 90-mlnute cycling loop.

“Turn off here?” I yelled back.

“Turn off here?” I yelled back.

“Keep goin’,” Kennedy grunted. “Old Camp’s six miles.”

After the Luge tumotf, the traffic on the Santiago Truck Trail almost disappears as the trail tightens. Suddenly, it’s more like real wilderness, overgrown in spots, so steep that you have to downshift into your easiest hill-climbing gears and concentrate on not falling over as you inch upward through 50-yard tunnels of branches.

After 30 minutes, I stopped and waited for Kennedy to catch up. When he didn’t show, I rolled a mile back toward him, only to recoil at the sight of a body sprawled in the middle of the trail. It was Kennedy — face up on the ground, and as helpless as a turtle on its back. He was squinting in pain, breathing heavily and clutching the pulled quadricep muscle in his right leg. Suddenly, this was no mere three-hour tour.

Out of riding shape due to the recent rains, unfed since the night before and not used to climbing nine nonstop miles and 3,078 feet of cumulative elevation gain, Kennedy had literally starved the glycogen fuel out of his muscles. As he moaned and stretched for 30 minutes, I grabbed an orange from my pack, peeled it for him, and did the math. “Hey, we always can do this next week and leave earlier,” I said, worried about freezing after sunset. I had three more oranges on me, but no jacket.

“Old Camp’s not far,” he said, hobbling to his feet. “I’ll just walk these steep parts, because I’ll blow again if I try to ride it.” So we pushed upward at an agonizingly slow pace. But it was worth it.

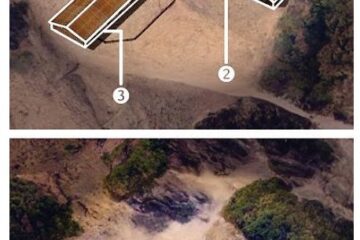

A Renoir painting. An Ansel Adams photo. Old Camp, located at the end of a 100-foot descent, is all of these — a mystical mountain meadow studded with oaks, vines and ferns astride the gurgling perfection of Santiago Creek In its post-storm glory. We sat on rocks, took off our shoes, and drank it all in like Tom and Huck on the Mississippi. Kennedy had been here before, but never with the stream running.

“Can you believe we live 10 miles from here as the crow flies?” I said. Home seemed a million miles away. And I felt like I was 10.

I vowed to return someday soon with my son Joey, 10 next month, and maybe even bring sleeping bags. You can stay overnight at Old Camp with a free permit from the Cleveland National Forest/Trabuco Ranger District, (951) 736-1811.

Before long, it was past 5 o’clock, and the race with the sun began. The nine-mile return trip, mostly downhill, normally wouldn’t have been a problem, except that the route also had half a dozen short, tough sections going uphill. Each one elicited a shriek of pain from Kennedy as he tumbled off his bike clutching rebellious sinew.

I could do nothing as he lay there in agony besides feed him pieces of orange and marvel at the wondrous sight of city lights twinkling against a sky changing from pink to bright red to purple to black. As his body betrayed him again and again, the clock struck 6, then 7 p.m. We took to slowly walking all the climbs, cursing ourselves for not carrying a cellphone, jackets or headlamps, and politely yukking as the last of the passing hikers delivered the standard joke about us being the evening’s “mountain lion bait.”

Luckily, we had moonlight, which illuminated our limp return. At 7:30 p.m., the only humans remaining on Modjeska Grade, we unlocked the SUV and headed back. “Well, was that enough ‘adventure’ for you?” Kennedy said as we drove back to civilization. He smiled the smile he wears when he makes a torn one-dollar bill reappear as a $10.