Because It Hurts

Mount Hood’s biking trails offer verdant glens, boisterous wildflowers, gawk-worthy views, and grueling days that cause exhausted legs to cry out in agony. And we want to do this again?

Source of this article: Sierra (Magazine of the Sierra Club), March 2009.

By Peter Frick-Wright

We’ve been staring at the map for an hour when we finally give up. Tracing and retracing tomorrow’s route with our fingers, we’ve talked through various sections of the trail, trying to deduce hidden meaning from the jumble of topo lines. But no matter how hard we look or how many times we count the contours, we’re baffled.

Billy Tufts navigates Pioneer Bridle Trail on the west side of Mt. Hood.

An hour ago we sat next to a healthy campfire, an ample stack of dry firewood on hand, lazily enjoying views of Mt. Hood’s western flank and evergreen-studded valleys while the setting sun slowly changed the flavor of the peak’s glacial topping from vanilla to strawberry.

Now my friend Billy Tufts and I recline in metal folding chairs, spooning a mash of refried beans, corn, and diced Spam out of a metal pot and congratulating each other on riding 46 miles of dirt roads and single-track trails, enjoying some hard-earned lethargy on the last night of a four-day hut-to-hut mountain-biking circuit around Oregon’s tallest peak. Then one of us brings up Post Canyon.

To ride Post Canyon means we’d voluntarily add 3,000 vertical feet of climbing to our last day on the trail, bagging the highest point on a spur that traverses some of the Pacific Northwest’s most severe topography. The alternative is a paved descent toward the brewpubs of Hood River. We are at an impasse, torn between resting our throbbing legs and enjoying an afternoon of single-track thrills.

We ask ourselves a question inherent to many outdoor adventure activities, one that is tough to answer honestly: How hard are we willing to work for our fun?

If we don’t ride Post Canyon, will we remember this trip for the three days when we successfully climbed every hill in our path and rose to meet each new challenge, or the fourth, when we skirted the final summit in favor of the paved road of least resistance? Then again, if we tackle the climb, will it be because we are tough and adventurous–or egotistical and stupid? Will it be worth it?

Hard as we look, the map offers no answers. Three days earlier the decision would have been clear.

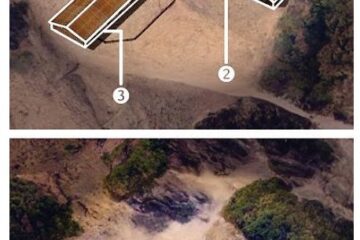

Clockwise from above: A view of Mt. Hood from within Mt. Hood Wilderness (an area off-limits to cyclists); Billy Tufts crosses White River; cozy quarters: the Surveyors Ridge hut; Tufts rides through a cluster of buckwheat on Surveyors Ridge.

Day One: As we climb out of Hood River, the relentlessly rising logging roads eat momentum and force us into lower and lower gears until pedaling seems futile and progress turns glacial. Many riders thrive on these climbs, when every second in the saddle is a testament to fortitude. But somewhere around mile 19, my lower limbs begin to mutiny.

“You spend too much time at your desk, word boy,” they say. “You’re not in the kind of shape it takes to enjoy riding these mountains. We might as well turn around.”

“Keep pedaling,” I tell them. “Only seven more miles to go.”

“But you spend much more time climbing than descending,” they say. “You’re the loser in this deal.”

“We are in the beautiful Mt. Hood National Forest,” I counter. “This is time well spent.”

“Even the best trails aren’t worth this much effort,” they moan.

“We’ll see.”

I would rather banter with Tufts, whom I met while working at a bike shop three summers ago. But he’s a transplant to Oregon from New Mexico, and like most things native to the desert, he’s made of sterner stuff than those of us from gentler climes. (He also had the bright idea to train for this trip.) I work hard just to keep him in view.

Tufts is the first to reach our hut that night, a solid one-room structure designed by James Koski and Don Bain, who founded the Cascade Huts trail system in 2007. (The duo persuaded national forest managers to allow them to plunk three huts along some of the forest’s lightly used trails. In winter they’re moved to Mt. Hood’s southeast side, where they’re accessible to backcountry skiers and snowshoers.) Eight bunks built of two-by-fours and plywood line the walls, with an open space in the center where a card table fits perfectly. When we get them lit, two lanterns on the far wall reveal hot plates, cookware, five-gallon jugs of water, eight sleeping bags with thick foam mats, and a large metal cabinet stocked with canned food. It’s spartan. But by backcountry standards, it’s cushy.

With food, water, and shelter waiting, the three huts allow mountain bikers to schlep minimal gear each day on the loop, saving their legs and energy for climbs. Unlike hut-to-hut rides on which guides drive gear to the next stop or follow in a support vehicle, we’re on our own. The route runs on the honor system. It’s up to us to navigate, cook, and get to the next hut before dark. Even if we’re not making great time uphill.

Day Two: We’re on the Surveyors Ridge Trail, loping between shade and sunshine, weaving through evergreens, and leaning way back as leafy plants reach into the trail and rake our shins. Popping up and down easy inclines in high gears, we pedal in short bursts and ride out the momentum. Mt. Hood peeks in on our fun from somewhere through the trees. The foliage alternates between desert brush and valley lush as we hop in and out of the mountain’s rain shadow.

We’re now on a trail too narrow for two bikes side by side. Single track brings everything closer and accentuates the illusion of speed. We hug corners as clumps of paintbrush, buckwheat, and lupine flash by in bursts of red, white, and blue. “Everything is better on single track,” Tufts yells out.

Eight miles later, however, the trail ends. We’re back on a dirt road, the memory of rolling single track drowned out by quads and calves complaining like spoiled children.

“Are we there yet?” they say.

We stop for our standard lunch of energy bars and Gu, an energy gel favored by triathletes. Gu is lightweight and portable and tastes like it was developed with those priorities in mind. Still, it’s a reason to get off the bike, and the blood sugar boost takes a bit of the edge off our effort.

Cresting a six-mile climb after our break, we start down a long, rocky road toward Gunsight Ridge. Halfway down, we pass three hikers who step to the side when they hear us coming. At the same time, we stop for the off-road motorcycle climbing the road toward us. We’ve gotten the right-of-way rules exactly backward. The hikers send us a nod.

Mountain bikes are often lumped in the same category as all-terrain vehicles, but research shows that mountain bikers and hikers do about the same damage to trails. Hiker-cyclist conflicts do erupt in more congested parklands closer to urban areas. But in this context, I take the hikers’ acknowledgment to mean “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

In fact, as long as riders don’t cross into Mt. Hood National Forest’s five wilderness areas, where federal law prohibits bikes, we’re free to improvise our own route. Our printed hut-to-hut directions are mere guidelines. We find four miles of single track that, on a topographic map, looks like it veers off the ridge, crosses White River, and deposits us within a half mile of the second hut. It looks fun, cuts miles off our day, and requires nary an uphill pedal. “Why,” we think, “wasn’t this included in the directions?”

Shooting down the forested trail, we’re up out of the saddle as we navigate rock gardens and tight switchbacks. Downed trees slow us for a moment, and then we’re back on the bikes, thankful for the morning’s slow, monotonous work that brought us here. At the bottom of our newest favorite hill, we discover that the trail doesn’t cross White River so much as White River crosses the trail. Stuck on the bank, preparing to wade across, it turns out we’ll be paying for our big fun with sopping sneakers and wet gear that will have to be dried out beside a campfire.

Across the stream and a half mile later, we stumble into the second hut soaked by sweat in some places and snowmelt in others. For me, the first order of business is the saltiest thing I can find: Campbell’s chicken noodle soup. I gulp the soup from the pan like it’s a jumbo drinking gourd. Next comes Gatorade from the powdered mix, then a can of baked beans and some fruit. That levels off the nutritional cravings and deficits for at least an hour while we heat up a main dish heavy on carbohydrates and protein. I’ve never seen bears raid a campsite, but I imagine it looks something like our arrival.

Day Three: Recovery time lengthens each day. This morning finds me particularly sensitive to my bike seat. As I finally and painfully settle into a pedaling rhythm, a vague creaking and moaning seems to creep into the forest. Either my bike is sore too or my bottom bracket is coming loose.

On a trip that pushes your endurance, when each decision is measured by its impact on vertical feet gained or lost, mechanical malfunctions are surprisingly easy to live with. Each time something goes wrong is a chance to rest. On a day with nearly 50 miles between beds, these breaks are dangerously welcome.

In fact, our fiddling and fixes distort our sense of time and distance so much that we start to think we’re closer to the third hut than we really are. In our minds, every trail junction becomes the second to last, and frustration ratchets up a notch every time a bend in the road fails to reveal home sweet hut.

When we finally do see the hut, it is the most splendid of the lot, framed by blooming rhododendrons with Hood’s volcanic crown towering regally above. We settle in to eating and doing nothing, then discuss the final day’s major route choice.

“To Post Canyon or not to Post Canyon?” I write in the hut’s logbook.

I like to think we would have chosen that final climb. But halfway to the decisive turnoff, I shift to power up a small hill. Pop! The trigger mechanism on my rear shifter is loose, dangling from the handlebar nearly useless. I can jiggle it to change gears, but it won’t last long. Like many choices delayed too long, ours is made for us.

We breeze into Hood River early in the afternoon. We obey stop signs and hug white lines around wide corners, our knobby tires humming against the pavement.

I bid Tufts goodbye and head home, back to work and challenges theoretically more subtle than icy rivers and arduous hill climbs. I planned to mount the trail maps on my wall, our route marked in red pen. But they’re still piled near the desk where I sit too much. I often find myself going back to the map of Post Canyon and folding away the others. I can kill an hour just staring.

Peter Frick-Wright is a frequent contributor to Sierra. A version of this article appeared in the Oregonian.

0 Comments