A war on urban coyotes escalates in the Southland

As eradication efforts grow, critics say coexistence is more realistic

Source of this article: The Los Angeles Times, September 21, 2022

Kristin Muller said she was sickened by the sight of the half-eaten remains of her cherished cat, Milkshake, on a neighbor’s lawn.

Security camera video, she told the Manhattan Beach City Council, revealed that Milkshake “was ambushed and killed from behind at 3:46 a.m.”

It was one of three cats her family believed were lost to coyotes in just two months in the city’s Liberty Village community, despite desperate efforts to protect them by dousing the yard with gallons of wolf urine.

“You can’t stop these horrific coyotes,” she told the council in June. “They remember. Then they come back and keep coming back every single night until they eventually catch their prey.”

The angry, tearful account was just one of a growing number of coyote horror stories that have echoed in municipal hearing rooms and over internet message boards in recent years — tales of bold predators that roam the back alleys and flood control channels of the Los Angeles Basin, attacking pets and humans alike.

The reports are fueling an escalating war on Southern California’s urban coyotes, and exposing deep divisions between those who want to eradicate the animal and groups such as Project Coyote that call for peaceful coexistence.

The widening coyote war is also raising fundamental questions for cities that have long struggled to manage their coyote populations. Those questions include whether local government should be involved at all, and whether such a tenacious and adaptive animal can even be controlled.

For answers, Manhattan Beach and some other communities are turning to Torrance City Councilman Aurelio Mattucci, who recently shepherded a measure that made his city one of the few in California committed to year-round trapping under a contract program that kills about one coyote a week using lethal injection.

“Coyotes may have been here first, but we’re here now,” Mattucci said in an interview in his office. “We want to make property safe for people and pets.”

Breaking into a smile, he added, “experts agree that a dead coyote is 100% less likely to reproduce.”

Mattucci, a real estate agent, is founder of the grass-roots movement Evict Coyotes and a spark plug among a new breed of hard-line activists who see a distinction between “wild coyotes” and those that have adapted to the clatter and commotion of life within the urban sprawl.

Evict Coyotes isn’t interested in the nonlethal hazing techniques promoted by animal advocacy groups, or the ecological importance of preserving a top predator within an urbanized food chain. Instead, members file into government meetings clad in bright red T-shirts stenciled with the message “Evict Coyotes” and demand that officials enact tougher anti-coyote laws.

Organized four years ago in Torrance, the group is active in such widespread communities as Manhattan Beach, Palos Verdes, West Covina, Walnut, Bellflower, Downey, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Carson, San Dimas, La Verne, Glendora, Escondido and Fullerton.

“The pendulum is shifting in a new direction,” said Steven Childs, a 46-year-old who created the website ProjectCoyoteLies.com. “People are frustrated with a coyote management issue that’s gone amok, and animal advocacy groups preaching an ideal that is unrealistic.”

Childs, who describes himself as a military veteran, hunter and “coyote investigator,” said what is really needed “is to let communities decide which coyote behavior is appropriate or inappropriate.” He would also like to see “a statewide coyote management plan that is grounded in science.”

The science on urban coyotes, however, is far from established.

For example, some animal advocates and biologists contend it is impossible to eradicate coyotes from a given area because they quickly rebound, so it makes practical sense to learn to coexist with coyotes.

Other scientists argue that coyote populations are naturally regulated by the availability of food and territory, so extermination campaigns, at least theoretically, could be effective in certain circumstances.

The pushback has wildlife advocates, including People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, the Humane Society of the United States and Project Coyote, on the defensive. For years, they have promoted coexistence, as well as hazing techniques to keep coyotes away and laws that would prohibit the feeding of wildlife.

“Personally, it’s unsettling — a little frightening, really — to see how fast untruths spread and get adopted, and by so many people,” said Rebecca Dmytryk, president and chief executive of the nonprofit National Assn. for Wildlife Emergency Services.

“I feel like there’s common ground somewhere, I just haven’t been able to find it yet,” she said. “Partly, maybe mostly, because the ‘other side’ doesn’t want to even have a civil conversation.”

Michelle Lute, a spokeswoman for the nonprofit Project Coyote, wouldn’t argue with any of that. “The coyote management practices we recommend are based on the best available science,” she said. “But they fall on deaf ears in a room full of Evict Coyote red shirts.”

Niamh Quinn places a radio collar on a healthy, 29-pound young male coyote captured and collared in Hacienda Heights.

Coyotes have been tracked, spotted and photographed in virtually all developed areas of Los Angeles County, whether darting between headstones in a Boyle Heights cemetery, foraging through trash on a sandy South Bay boardwalk, or loping across a middle school athletic field in Paramount.

“If you have green spaces in your city, you have coyotes,” said Niamh Quinn, one of a small number of researchers who track and study urban coyotes. “In fact, you could probably find coyotes making nighttime visits at almost every schoolyard in L.A. County.”

Despite their ubiquity, the size of the coyote population in L.A. County remains unknown. (The state Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates that there are 250,000 to 750,000 coyotes statewide.)

Quinn, UC Cooperative Extension’s human-wildlife interactions advisor, has learned a lot about urban coyotes by following the GPS pings of collared animals.

![]() “Urban coyotes really are different than coyotes in wilderness areas,” she said. “I doubt an urban coyote would survive very long in the wilds.”

“Urban coyotes really are different than coyotes in wilderness areas,” she said. “I doubt an urban coyote would survive very long in the wilds.”

Her postmortem research into the contents stewing in the stomachs of urban coyotes that perished across Los Angeles and Orange counties under myriad circumstances revealed a smorgasbord of samplings: cottontail rabbits, birds, potato bugs, avocados, oranges, peaches, watermelon, cats and an occasional dog. They also tolerate the taste of candy wrappers, fast-food cartons and hiking boots.

Urban coyotes also roam widely.

Scientists still talk about C-146, a female subadult coyote. In the short time National Park Service biologists tracked her movements via a GPS collar, her wanderings displayed strikingly unusual behavior for a species that is territorial.

Collared in northeast Los Angeles on Sept 23, 2015, C-146 traveled as far south as downtown via the Los Angeles River; wandered throughout Elysian Park, near Dodger Stadium; and ventured into the Westlake neighborhood, where she met an untimely fate in MacArthur Park.

On Dec. 4 of that year, her carcass was found soaking wet and covered in algae near the park’s lake. A necropsy identified the cause of death as drowning but also detected high levels of anticoagulant rodenticide in her liver.

Why she went into the lake remains a mystery, but scientists speculate she may have fallen in while trying to get a drink. Animals commonly become thirsty when exposed to rodenticides.

While the presence of coyotes in a neighborhood may concern many people, “they are not a threat to public safety,” said Victoria Monroe, a conflict programs coordinator at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The possibility of misunderstandings and potentially dangerous conflicts are increased in urban settings, however, because coyotes display seasonal shifts in their behavior.

Mating season generally runs from late January to early March. During this period, state wildlife authorities say, coyotes are in search of a den and male coyotes may become more aggressive and territorial, which poses a risk to people and household pets.

Residents are also likely to see an increase in activity between early spring and the fall, when females begin giving birth to pups that remain with their mothers for about six months while learning to fend for themselves.

Keeping a dog on a leash generally reduces the risk of coyote attacks, wildlife officials say.

In calling for the eradication of coyotes, Mattucci and others point to a historical record of attacks, including the 1981 killing of a 3-year-old girl in Glendale — the only documented case in the country of a coyote killing a human.

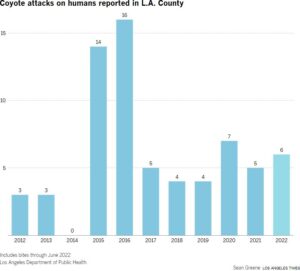

More recently, at least 69 people were bitten by coyotes in Los Angeles County between 2012 and 2022 — about half of them in communities east of downtown, according to the county Department of Public Health.

About 20% of those bites occurred in Elysian Park, just north of downtown. Twelve people were bitten there in 2015 alone, and most of those attacks were unprovoked, the department said. Victims included a jogger, a child who had been playing with friends and two people who were sitting on the ground and looking up at the stars.

About 20% of those bites occurred in Elysian Park, just north of downtown. Twelve people were bitten there in 2015 alone, and most of those attacks were unprovoked, the department said. Victims included a jogger, a child who had been playing with friends and two people who were sitting on the ground and looking up at the stars.

The motivation behind that string of attacks remains unclear. Some scientists speculate that they may have involved a lone coyote that had lost all fear of humans.

But coyote attacks have continued at Elysian Park — perhaps, some experts suggest, because someone has been feeding the animals, resulting in a dangerous situation for people and pets, as well as coyotes.

Two recent incidents at Elysian Park included a child bitten on an arm in May, and an attack archived by county officials under this description: “Child bitten while walking in park carrying small dog. Child bitten on right leg, dropped the dog, which coyote took and ran away.”

Those who argue that people and coyotes can coexist say such incidents are the result of humanity’s unreasonable expectations of nature.

Chase Niesner, a PhD candidate at the Institute for the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA, has coined the phrase “cloud coyotes” to describe the disharmony between urban dwellers and the intelligent predators that have lived here for 47,000 years.

Ambling down a path on a recent morning at one of his favorite coyote hangouts, Evergreen Cemetery just east of downtown, Niesner said cloud coyotes are animals that inhabit the virtual worlds of chat threads and social media platforms, but not the real world.

Often, these cloud coyotes are depicted as terrifying phantoms that threaten the sanctity of homes and yards, eat pets and attack children with impunity.

By Niesner’s reckoning, cloud coyotes don’t stay in apps like Nextdoor. They trot from images captured on camera phones to neighborhood gatherings to government hearings to lethal extermination campaigns.

“They are manifestations of people’s need to domesticate every square foot of space in the region,” he said, “to the level of comfort and safety they feel within their own homes.”

An ongoing study conducted by Niesner, Christopher Kelty and Spencer Robins suggests that the same survival skills that enabled coyotes to outlast federal extermination campaigns during the 19th century has allowed them to flourish in some of the most densely populated urban centers in the world.

A coyote’s senses are always on extremely high alert for both prey and potential threats, they say, because they evolved as prey for North America’s gray wolves, which were nearly wiped out by the 20th century.

Today, the coyote’s lunatic “yip, yap yahoooo!” is heard throughout the U.S. and Canada because there are more of them than ever, despite attempted eradication by poison, mass shootings, lethal injection and toxic gas.

“Whereas in the rural American West of the past, protecting ranchers’ livestock provided the main impetus for killing coyotes, today it is private urban and suburban homeowners and their beloved cats and dogs who are on the front lines of settler colonialism,” they wrote.

Niesner, who belongs to an emerging school of conservationists who see cities as the frontiers of nature in the 21st century, does as much as he can to introduce people to real coyotes instead of cloud coyotes.

“Many people relate to nature — whether it’s rattlesnakes, pine trees or squirrels — by wanting to see it and then decide whether it’s worth sharing space with,” he said.

When he wants to introduce people to his favorite bands of urban coyotes, he takes them to pockets of gated terrain such as Evergreen Cemetery’s 115-acre expanse of weathered gravestones, obelisks and majestic oaks framed by the 101, 60, 10, and 5 freeways.

“These coyotes moved into the cemetery about a decade ago,” he said, “and locals don’t seem to mind.”

0 Comments