A Cast of Characters: The Creation of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area

Source of this article: KCET.org, June 25, 2015

The public is so often chastised for not really hanging in to achieve action on a particular cause. This reaffirms the need for really hanging in. All those people who worked — for that length of time — did it. – Margot Feuer

Many Angelenos are unaware of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area’s existence, but almost all of us have enjoyed it. It is the world’s largest urban national park — comprised of 153,075 acres of park land, with holdings that stretch across five zip codes. This patchwork of parks run by national, state, and local agencies includes such varied destinations as Paramount Ranch, Runyon Canyon, and Will Rogers State Historic Park, as well as miles of beaches from the Santa Monica Pier area through Malibu to Mugu Lagoon where the mountains taper off into the Oxnard Plain. Its creation in 1978 was the result of years of grassroots activism, political machinations, and public debate performed by a cast of often contentious characters as varied and exceptional as the natural areas they helped preserve.

So who can claim the most responsibility for the beginning of the movement to preserve the Santa Monica Mountains, which stretch from the Hollywood Hills to Point Mugu in Ventura County? “I think it’s both a who and a what,” said Woody Smeck, superintendent of SMMNRA from 2001 to 2012. “Because the who were responding to what was happening in the Santa Monica Mountains.”

“What happened was that in the 1950s, there was an interesting combination of technology and development,” explained Joe Edmiston, the charismatic and controversial executive director of the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority, a land acquisition and conservancy agency who works in close partnership with SMMNRA. Before World War II, the Santa Monica Mountains were almost untouched, and exclusively the haven of the very well to do. During WWII, many innovations, especially the D-9 caterpillar, “reduced the cost of moving the earth around dramatically,” according to Edmiston. Post-war California boomed; developers made fortunes building housing developments, while contractors sought government contracts to build the massive California freeway system, which soon became famous the world over. Mountain ranges were “day-lighted,” meaning that their tops were shaved off and their canyons were filled in. Large developments were often built on top.

During the late ’50s and early to mid ’60s, a number of development proposals for the Santa Monica Mountains alarmed the public, newly sensitized to environmental issues by cultural touchstones like Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring.” In an effort to reduce pollution and stop the private home use of smog causing trash incinerators, one city councilman proposed filling many of the ranges’ canyons with city landfills. These landfills would then be converted into golf courses with developments around them. Caltrans proposed major freeways that would run through Malibu Canyon. A nuclear power plant was also proposed for Malibu. The beaches of Santa Monica and Malibu were being transformed from egalitarian public playgrounds into private havens of the ultra-rich and the comfortably retired. According to Edmiston, a short film that documented the leveling of mountains to create the Beverly Glen neighborhood caused a sensation, as did an article in Frontier magazine claiming that the creation of Beverly Glen signaled the end of the Santa Monica Mountains.

In different pockets of Los Angeles, public dissent began to brew, and the idea of protecting the mountains by turning them into a chain of public parks began to be floated. Across the political and sociological spectrum, the cast of “who” began to take shape, eventually numbering in the thousands.

One of the earliest activists was a wealthy biking enthusiast from Brentwood named Marvin Braude, whose name graces the local 20-mile coastal bike trail. Braude began hounding the city to buy as much of the mountains as possible to save them from development. By 1965, the “cantankerous” and “professorial” Marvin was tired of being ignored by the pro-development city council, so he ran himself. He won, primarily because of the public’s growing objection to the proposed Santa Monica Mountains highway. For the next thirty-two years he would be a tireless champion in the fight to preserve the mountains for future generations.

Often called “the mother of the SMMNRA,” Sue Nelson got involved with community activism while raising her children in the early ’60s. In 1964, she helped found the Friends of the Santa Monica Mountains, Parks and Seashore, and would soon become the organization’s president. The feisty, somewhat ruthless Nelson lobbied constantly for the creation of the park. “She was a very warmhearted person and very supportive of people who were trying to accomplish something worthwhile,” one associate told the Los Angeles Times. “At the same time, no matter who you were, she could explode at you.” Nelson was a master lobbyist and formed many close bonds in Sacramento and Washington. Margot Feurer, a longtime environmental activist from Malibu, lobbied alongside Nelson as the Sierra Club’s principal lobbyist.

Many Angelenos were brought into the fight by Jill Swift, a stay-at-home mom and Sierra Club member. An avid hiker, Swift formed the Santa Monica Mountains Task Force to help save the mountains she loved. Swift, who Woody Smeck called a “true naturalist” with “an amazing knowledge of the environment down to the smallest details,” began leading popular hikes into the Santa Monica Mountains to educate people about the wonders of the endangered area. These excursions became important consciousness raising events. A 1971 “March on Mulholland,” protesting the proposed paving of a scenic portion of Mullholland Drive, drew over 5,000 people. The road remained unpaved.

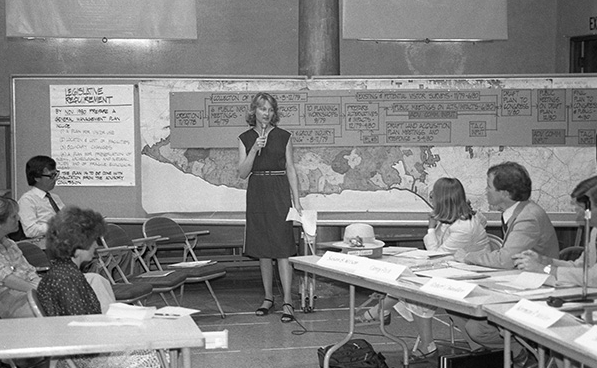

The movement to save the mountains had picked up significant steam by the early seventies. It was aided by the growing mainstream popularity of environmentalism and a strong anti-development sentiment. These cultural shifts helped achieve the passage of the Coastal Zone Conservation Act (Prop 20) in 1972, and the California Coastal Act in 1976. In the state senate that same year, Representative Howard Berman of Hollywood Hills pushed through legislation to create the Santa Monica Mountain Comprehensive Planning Commission (forerunner to the MRCA), an advisory committee tasked with coming up with a master plan for the mountains. Joe Edmiston, then a clever young Sierra Club lobbyist, was put in charge of the commission, making him the youngest head of a state agency.

In Washington D.C., a bill calling for the creation of a Santa Monica Mountains National Park was drafted in 1977. Freshman Representative Anthony Beilenson (D-Woodland Hills), often called “the father of the SMMNRA,” worked closely with the indomitable Sue Nelson to write the bill. “She was very much the single greatest private force behind our working to create the park,” Beilenson remembered.

But it was a strange political twist of fate that would finally make the SMMNRA a reality. Into our story enters the legendary “raging” liberal, Representative Phil Burton of San Francisco. A product of the old Irish political machine, Burton was a larger than life character. He was also considered by many to be a political genius. In 1976, Burton was up for election for Majority Leader of the House. Considered a shoe-in, he ended up losing by a single vote. Overnight, his political stock dropped dramatically.

However, Burton rebounded quickly. As Chairman of the House subcommittee of National Parks and Insular Affairs, he quickly began amassing new power by crafting a giant omnibus national parks bill, often derisively called “the park barrel bill.” By the time it was debated on the floor, one politician sniffed to Edmiston, “There’s something in this bill for every state and every congressional district!” Included in the bill was a provision establishing SMMNRA. This section of the bill was crafted by Beilenson, with input from Representatives Barry Goldwater Jr. of northern L.A. County and Robert Lagomarsino of Ventura.

The bill passed. Margot Feurer got the call from Washington, and delivered the news to an excited group of Westside Activists, many of whom had devoted over a decade to the cause. On November 10, 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed the National Parks Bill. What did this mean for the Santa Monica Mountains? According to a “Touch of Wilderness,” a just-published oral history of Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, it meant this:

The law created a 150,000-acre preserve that sprawled from Franklin Canyon above Beverly Hills to Point Mugu in Ventura County. It gave to the Secretary of the Interior the responsibility of managing the recreation area — to protect the scenic, recreational, educational, scientific, archaeological, historic, and public health aspects of the Santa Monicas, as well as its unique Mediterranean chaparral ecosystem. Congress set a ceiling of $125 million for land purchases over a five year period. The law placed the recreation area under the stewardship of the National Park Service…The SMMNRA was situated within a teeming metropolitan region, it encompassed many private land holdings, and the law mandated a federal partnership with state, county and local government jurisdictions. This combination made it almost unique among National Park holdings.

Edmiston recalls that the actual boundaries of the SMMNRA were drawn up during a meeting with many passionate activists, including himself, Sue Nelson, and an exasperated Phil Burton:

Burton says,“Now what’s the boundary?” Well, the National Parks Service had a boundary and Sue Nelson… she had a boundary, and the Santa Monica Mountains Planning Commission had a boundary and our boundary was larger in some areas than others. And at that time, this was before computers, so all this was on tissue paper. So they laid out the base map which is a bunch of USGS maps taped together and they said, “Parks commission lay out yours, ok Sue you come lay out yours, and Joe lay out yours.” And we start arguing, “I want to include this, I want to include that,” and Burton says, “give me marker!” and he draws an outline and it’s the exterior boundary of everybody’s map. He hands the marker back and says, “There!” And nobody could argue because everybody got what they wanted and it also included some stuff from the other guy. It was classic Phil Burton. And that’s the map.

The establishment of the park, though a great moral victory, turned out to be just the beginning of the struggle. Over the next few years the park faced many challenges, including its virtual defunding, challenges from developers, and lack of federal support. Joe Edmiston (whose MRCA has engaged in numerous land purchases on behalf of SMMNRA), Sue Nelson, Margot Feurer, Jill Swift, Howard Berman and Anthony Beilenson continued to work on behalf of the park, fighting developers (and often each other), and guiding the park to maturity. All three women and Burton have since passed away.

Today, SMMNRA continues to grow and change. This patchwork of parks is run by a patchwork of government agencies, and supported by numerous public and private entities. “When you look across the country this has to be one of the great bootprints for cooperative conservation between private, local, state and federal entities.” Woody Smeck said recently, “I think the record is pretty phenomenal.”

Special Thanks to Woody Smeck, Joe Edmiston, and Kate Kuykendall

About the Author

Hadley Meares is a writer, historian, and singer who traded one Southland (her home state of North Carolina) for another. She is a frequent contributor to Curbed and Atlas Obscura, and leads historical tours all around Los Angeles for Obscura Society LA

0 Comments