Middle of Nowhere Is a Center of Conflict

A federal plan allows more recreation and mining in a rugged land of national monuments.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, April 19, 2006.

By Julie Cart, Times Staff Writer

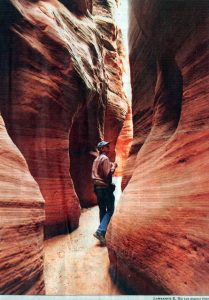

REMOTE PRESERVE: Rick Moore of the conservation group Grand Canyon Trust examines an area of Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, one of two preserved areas in the Arizona Strip.

VERMILION CLIFFS NATIONAL MONUMENT, Ariz. — The 3 million acres of federal land in the Arizona Strip have their remote geography to thank for preserving their spectacular red sandstone escarpments, slot canyons, rock art and ruins of ancient pueblos.

One of the last places in the Lower 48 to be mapped, the strip, in the northwestern corner of the state, is today bypassed by major highways and mostly devoid of gas stations, hotels and other visitor services. As a result, more than 12,000 years of human history written on this rugged landscape has remained in place, undisturbed by tourism or development.

That is about to change.

Here at the backdoor of the Grand Canyon, two national monuments, Grand Canyon-Parashant and Vermilion Cliffs, are poised to absorb the effects of the explosive growth from Las Vegas to the west and St. George, Utah, to the north — two of the fastest expanding areas in the nation.

The federal agency that oversees much of the land in the Arizona Strip, the Bureau of Land Management, is preparing a long-range plan for the area that would allow uranium mining and oil and gas exploration across 96% of the lands outside the monuments. The plan would also permit livestock grazing in the monuments and open 3,000 miles of roads to motorized recreation, including some in the monuments. A 7,100-acre “play area” for dirt bikes and all-terrain vehicles would be established. And although that area would be outside the monuments, it would be next to land set aside to protect a threatened cactus and a Native American petroglyph site.

Critics, including the Environmental Protection Agency and the local County Board of Supervisors, say the agency’s plan fails to protect the two monuments with their thousands of historic and cultural sites, and exposes fragile BLM lands to nearly unrestricted livestock grazing and recreational activities.

Others say the proposal won’t safeguard rare plants and animals, such as the desert tortoise and 20 species of raptors and other birds, including a colony of California condors reintroduced at Vermilion Cliffs.

“What you have in the Arizona Strip is a kind of sleepy place that has been highlighted with two monuments, but the BLM hasn’t really risen to these different challenges,” said Martha Hahn, a former BLM administrator with 21 years at the agency. Hahn now works with the conservation group Grand Canyon Trust.

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE: The view from the Vermilion Cliffs in the Arizona Strip, where the U.S. Bureau of Land Management is proposing broad changes. (Lawrence K. Ho / LAT)

But current BLM officials say the plan, which is four years in the works and won’t be finalized for months, is a commendable effort to reconcile the agency’s tradition of various uses on public land with its newer mandate to conserve national monuments.

“It’s all about finding the right balance between protecting the resource and allowing the public to use the land for grazing and other activities,” said Scott Florence, the BLM’s district manager for the Arizona Strip.

The Arizona Strip was cut off from its surrounding area by the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River until a ferry was established in 1871, which remained the only river crossing until the first bridge was built 60 years later.

After ancient Pueblo people settled on the mesas and in the canyons, only the intrepid passed through here: Spanish friars in the 18th century, wayward mountain men, scattered trappers and, in the 19th century, Mormon families guiding wagons along the Honeymoon Trail to St. George.

In 2000, President Clinton created the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, at just over 1 million acres, and the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, at nearly 300,000 acres. The BLM manages another 1 1/2 million acres in the area that don’t carry the same level of protection.

The presidential proclamations called the monuments geological treasures. The one for Vermillion Cliffs reads: “Full of natural splendor and a sense of solitude, this area remains remote and unspoiled, qualities that are essential to the protection of the scientific and historic objects it contains.”

Up to now, the Arizona Strip has been administered under a 1992 management plan. The proposed plan is the first to take into account the monument designations. Much of the land within the national monuments was intended to be set aside for scientific study, but BLM budgets often fail to make room for expensive scientific analysis. To survey the sites in Grand Canyon-Parashant, for example, would cost $30 million, according to Diana Hawks, who leads the BLM’s planning effort.

According to an article in the latest edition of Issues in Science and Technology, published by the National Academies and the University of Texas at Dallas, only 6% of the BLM’s 260 million acres in the West have been surveyed for cultural resources. About 263,000 cultural sites have been found, according to the article, but archeologists estimate there are likely to be 4.5 million sites on BLM holdings.

The pattern is repeated here. More than 97% of the land within the monuments has not been surveyed for archeological or paleontological sites, and according to a scientific study conducted last summer, 63% of the sites in Grand Canyon-Parashant are vulnerable to damage by off-road vehicle routes, as are nearly half the sites in the more remote Vermilion Cliffs monument.

“These archeological sites are a nonrenewable resource. Once they are gone, they are gone forever, ” said Peter Bungart, a Flagstaff-based archeologist who conducted last year’s monument surveys. “The silent history that’s on that landscape is important, unless you argue that history is not important.”

The BLM’s new plan concludes that none of the proposed activities in the monuments would damage resources. But critics contend that the agency can’t claim that roads won’t damage archeological resources, considering the BLM doesn’t even know where all of the sites are.

On a recent tour of Vermilion Cliffs, Rick Moore of the Grand Canyon Trust pointed out many archeological sites near roads, especially vulnerable to vandals. He showed one site atop the Paria Plateau where a road sliced though remnants of an early pueblo, the ruin’s low stone walls flanking the dirt road.

On a recent tour of Vermilion Cliffs, Rick Moore of the Grand Canyon Trust pointed out many archeological sites near roads, especially vulnerable to vandals. He showed one site atop the Paria Plateau where a road sliced though remnants of an early pueblo, the ruin’s low stone walls flanking the dirt road.

The Coconino County Board of Supervisors is particularly concerned about the web of new roads open in the monuments and the other BLM lands.

“We have ample evidence that misuse of the land in these landscapes is sometimes irreparable, and sometimes it ain’t gonna be right in your lifetime,” Supervisor Carl Taylor said.

Taylor said the prospect of renewed uranium mining has created a rush to stake claims on the western side of the Arizona Strip and that the activity would create even more roads.

According to the EPA, the BLM’s plan would open nearly nine times more public land to off-road vehicle use.

The EPA also argued against off-road travel in desert tortoise habitat and recommended that the BLM “eliminate open motorized and mechanized cross-county travel due to substantial impacts from this activity on soils, water resources, cultural resources and wildlife.”

Proponents of motorized recreation, on the other hand, fear they will lose some of the freedom they enjoyed before the monuments were created.

“What we’re worried about is that traditional routes are going to be closed, somewhat arbitrarily,” said Dale Grange of Hurricane, Utah, president of the Tri State ATV Club and the motorized recreation representative at BLM meetings. Grange said motorcycle and ATV rallies in the Arizona Strip draw hundreds of participants. But because of BLM restrictions, organizers have to turn people away.

The BLM’s Florence said the management plan for the area, though not perfect, is the result of years of careful, ongoing study.

“We fully expect to make some changes, clarifying what the plan does in term of protecting monument objects,” he said. “It needs to be more clear, building in specific details exactly how the monument objects will be protected.”