Roll over, Moab

Christopher Reynolds takes the wild ride into Copper Canyon.

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, April 12, 2005.

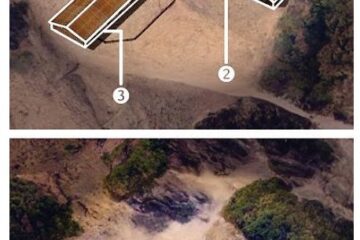

Dust devils: For centuries, only pigs, mules and the Tarahumara Indians blazed the trail of Mexico’s monster Copper Canyon – which is bigger than the Grand Canyon. Then American mountain bikers stumbled on to some of the deepest downhill runs in the work, and a Moab in the making

By Christopher Reynolds, Times Staff Writer

The shrine of the Virgin Mary is the tip-off: It’s all diabolical from here.

My bike and I have been skidding and sliding for an hour on this one-lane, dirt-and-rocks, switchback-ridden road, an epic abyss yawning on my right flank, then my left, then my right again. The boulder-and-cactus panorama is unmarred by guard rails or anything that might interrupt a fatal fall.

But the steepest stretch comes just after the roadside shrine. In the next nine skittering, jouncing, knuckle-whitening, pebble-spitting miles, I’ll be sinking 3,000 feet.

On the way down, I dodge jaywalking goats and mules, a couple of roaring motorcyclists, a dozen Tarahumara Indians on foot, one or two cowboys on horseback, a couple of rattletrap trucks and three snuffling pigs. Through layers of climate, history and culture I hurtle, hand-brakes clenched in each fist, Larry Kloet’s dust between my teeth.

I’d like to tell you Kloet, who is only inches ahead of me, is a famed off-road downhiller, but no, he’s a tall, gangling 54-year-old environmental engineer on holiday from Atlanta.

“I’m really not much of a mountain biker,” he tells me later. “I’m more of a road biker.”

Kloet was looking for a nature-and-culture outing, a departure from Georgia blacktop. He wound up in Copper Canyon, about 250 miles south of the U.S. border, a day’s travel from the nearest commercial airport.

The canyon, which is really a collection of seven great gashes between stony, carrot-hued walls of the Sierra Madre Occidental range, more than fits his topographical bill.

As millions of Mexican schoolchildren could tell you, it’s deeper than the Grand Canyon, and, depending on who’s counting, it covers twice as much territory, or four times, or 10 times. The big ditch up in Arizona gets no deeper than about 6,030 feet. Here the slopes drop 6,135 feet from promontory to valley floor. And, best of all, you’re allowed to ride here.

This is the type of plunge mountain bikers notice, and from the trails to the towns, there are signs of a hub in the making.

We started this morning about 7,500 feet above sea level, in thin air and cool mountain breezes. We’ll wind up in the subtropics, where the air is 20 degrees warmer, and the Batopilas and Urique rivers rush along the canyon floors. And as is becoming increasingly clear, Kloet will be there first.

He flies like a stork taking wing, his 6-foot-4-inch frame folded around the battered metal skeleton of a rented mountain bike. His off-road rashes from yesterday are healing nicely. I grind my teeth and settle into my own abrasive rhythm. Ride, fall, bleed. Ride, fall, bleed.

“I don’t like it when both wheels are skidding at the same time,” says Kloet’s trail mate from Georgia, Nancy Wylie.

“That means you’re going too slow,” Kloet says. Then he leaves us in the dust.

A new hub surfaces

Once upon a time, there was a town in Utah called Moab, a red-rock desert hamlet known for just one thing: uranium mines. Then somebody noticed all those old mining roads and the way a set of knobby tires could grip that red rock, and pretty soon Moab was mecca for mountain bikes.

Once upon a time, there was a town in Utah called Moab, a red-rock desert hamlet known for just one thing: uranium mines. Then somebody noticed all those old mining roads and the way a set of knobby tires could grip that red rock, and pretty soon Moab was mecca for mountain bikes.

Copper Canyon, says Chuck Nichols, “is another Moab waiting to happen.” And Nichols, 55, has seen a lot of both places. He and his wife, Judy, opened the Poison Spider bike shop in Moab 15 years ago and watched as mountain bikers took to their red-rock town like ants to flan. Since 2001, through their company Nichols Expeditions, the two have been bringing a U.S. group to Copper Canyon every year.

Until now, if you’ve heard of Copper Canyon at all, it’s probably because of the railroad — a 400-plus-mile trip from Los Mochis to Chihuahua full of tunnels, twists, track-side vendors in native garb and hints of the territory’s history as a gold- and silver-mining region in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But more and more Mexican and American bikers are turning up these days, drawn by some of the deepest downhill runs in the world and a trail network blazed by generations of Tarahumara. The result is a landscape full of lethal vistas, backcountry characters and ancient ways.

Kloet and Wylie booked their way here through American tour operator REI Adventures. Another dozen riders, traveling with Western Spirit Cycling Adventures, are already down on the canyon floor. Both companies started bringing cyclists here in 2004.

Some drive from Tucson or El Paso, so they can bring their own hardware. Others fly into Los Mochis, near the Pacific coast, take the trains, then rent bikes. On the main drag in Creel, the canyons’ gateway town, bike-rental income for Tres Amigos Canyon Expeditions’ bike shop was $150 in July 2003 and $1,500 in July 2004.

Cyclist and guide Arturo Gutierrez, who started a summertime mountain bike competition in the mid-1990s, has seen it mushroom from 70 riders to more than 400 last year. This summer, the 37-year-old Gutierrez, who also guides trips for outside companies and runs a bike tour operation called Umarike Expeditions, is forecasting 800 competitors.

For Kloet, it’s a whole new world of biking. He eludes a belligerent cow at the canyon bottom, then presses on as the other bikers halt to gobble snacks, admire the deep green Batopilas River and pile into a pair of following vehicles.

“Best ride I’ve ever done,” says Cindy Crean, 41, of Connecticut.

Kloet, meanwhile, is on the heels of Gutierrez. Through another 10, 15, 20 miles they pedal on along the rising, falling, narrowing, twisting road. At last the two reach the entrance to downtown Batopilas, the 800-soul town, founded by silver miners in 1709, that serves as the center of canyon-floor civilization.

This is a good piece of riding, Gutierrez says later. But the real test, he whispers, will be the climb back out.

Most riders don’t even try, or make it less than halfway. From canyon floor to the beginning of paved road, it’s about 40 miles, including some 9,000 feet of climbing. Nine years ago, Colorado-based mountain-biking champion Sarah Ballantyne made the climb in about 4 1/2 hours, says Gutierrez, and most strong riders take five or six.

For Kloet, there’s only one way to find out.

The road from Creel to Batopilas is the marquee attraction of Copper Canyon mountain-biking. But for more technical thrills, dodging boulders, ducking branches and clinging to single-track paths, riders head for obstacle courses such as the aqueduct path on the Batopilas canyon floor or, up near Creel, the Valley of Monks, the Ejido San Ignacio. Or there’s Cusárare Falls, where a rock-strewn two-mile route leads to a waterfall 90 feet wide and almost as high.

“There are trails that are 8,000 years old, trails that go everywhere, from the Tarahumara and the people who came before them. None of them are marked,” says Nichols, exaggerating only slightly.

“It’s like Thailand,” says Western Spirit cycling guide Scott Davis, thinking of steep, thickly vegetated slopes and ancient neighboring culture.

“There’s some places that remind me of Alaska,” says rider Sylvia Muñoz, who lives in Fairbanks, thinking of the jagged high ground.

“I did the North Rim of the Grand Canyon last year, but we had to stay on the rim,” says rider Valerie Van Cleave, 54, of San Rafael. “You just can’t compare this.”

By the time I find these three, grinding away one morning outside Batopilas, they’ve spent most of a week on Copper Canyon trails.

Though the landscape between Creel and Batopilas shows few obvious signs of environmental damage to a newcomer, the mining and logging industries have had their way here for more than a century.

Only one relatively small portion of the area is designated a national park, with much of the rest of the land communally owned by families that have farmed or logged here for generations. Those same families have kept the trail network operating with their daily travels on foot and horseback.

When I ask if anybody worries about bikes doing damage to the terrain, the locals look at me as if I’ve just voiced concerns about stray comets. Amid these sudden cliffs and cactus spines, protecting yourself from the landscape is still a far higher priority than protecting the landscape from yourself.

One afternoon, guides Gutierrez and David Baeza pull on their bright biking togs and take to the aqueduct trail, its cobblestones-and-mud-puddle path lined by mangoes, potatoes, peanuts, oranges and grapefruits of farmers.

There are no other bikers — but there are chickens, pack horses, scythe-wielding farmworkers and 66-year-old farmer Fernando Torres Ruelas, who grins at the riders’ outfits and spins tales of the great flood of 1943.

The scene makes a poster picture of back roads mestizo Mexico, part old agriculture, part new tourism. But look far enough down the trail, in either direction, and you find another civilization entirely: the Tarahumara.

They number about 50,000. They farm, whittle wood, weave baskets, sell crafts in the towns and walk miles and miles in brightly dyed fabrics and sandals made from recycled tires. Once or twice a year, the Tarahumara join in epic trail events of their own, kicking little wooden balls on paths for as long as two days straight. On a race of more than 100 miles, few on Earth can match the swiftest Tarahumara. Yet between races, several locals told me, nobody trains — they just walk, hour upon hour, up and down these killer slopes.

When Tarahumara men cross paths, anthropologist William Merrill wrote in the 1980s, their most common morning greeting is “What did you dream last night?”

Tarahumara kids seem more interested in reality. They want pencils, candy or a chance to check out a foreigner’s wheels. Because even the Tarahumara have been buying bikes.

“They’re not the most expensive mountain bikes, but functional machines with a fat tire,” Gutierrez says.

Just as the Tarahumara see the world a little differently, they handle their wheels their own way. Many Tarahumara bikes have neither hand-brakes nor pedal brakes. To slow down, the kids stand up on the pedals, bend a knee and reach one foot behind the seat, like a napping flamingo. Then they press their tire-tread sandal against the rear tire, applying rubber tread to rubber tread. And they do it with absolute ease.

In the Casa Morales general store in Batopilas, proprietor Gustavo Morales has added a mountain bike to the floor display. Priced at $120, it sits next to a $300 leather horse saddle. In the last year bikes have been outselling saddles.

“There are still plenty of Tarahumara who double-take on us,” says Quentin Keith, co-owner of another company, Colorado-based Outpost Wilderness Adventure, bringing American bikers here. “But when we go into town, the little kids from the schoolhouse come up, and you hear them talking about suspension. They know.”

On his third and last morning in the canyon, Larry Kloet wolfs down an early breakfast, pulls on his helmet and sets off. Up until now, he’s denied any particular skill or ambition, but that doesn’t fit the description of the relentless churning fiend in the saddle now. He grinds his way from town to the hamlet known as La Bufa. He makes the bridge over the Batopilas River, where the serious climbing starts. Then he goes to war with gravity.

For those who aim to make this place into a Mexican Moab, the future must look something like that ragged, uphill route ahead of Kloet.

It’s been about 20 years since the first mountain-bikers found this territory and started talking up its possibilities. By the 1990s, a pioneering entrepreneur named John Saliba was bringing American mountain bikers almost every month in winter. Then two years ago Saliba died suddenly, at 33, on a trip to Thailand. To some degree, the American tour operators are picking up where Saliba left off.

Several guides say they see big possibilities in a long-idle 130-mile trail that mule teams once used to carry silver from the mines in Batopilas to the bank in Chihuahua. A bike-and-hike expedition reblazed the trail in November — a dollop of government funding is rumored to be on the horizon — and Outpost Wilderness Adventure may add it to their trip schedule next winter.

Meanwhile, mountain-bike pros Hans Rey, Brian Lopes and April Lawyer brought the daredevil seal of approval to Copper Canyon with adventures two weeks after my visit.

Rey and company spent three days on a backcountry footpath to Batopilas known as the Chinivo Trail, apparently the first time mountain bikers have covered those 40 miles.

“It can be very challenging, partly because of the altitude,” Rey would say later. “The trails we chose were made for donkeys and hiking…. But it’s such a vast area. And there’s the whole cultural experience.”

Rather than Moab, “it reminded more of a mix between Central California, like the Donner Pass area, and riding in the Arizona desert…. You’re really in a different world.”

Rather than Moab, “it reminded more of a mix between Central California, like the Donner Pass area, and riding in the Arizona desert…. You’re really in a different world.”

But none of this means the trails are teeming. Though the Mexican interior is crawling with Americans who sleep soundly in $12 backpacker lodgings, most would sooner fill their iPods with Milli Vanilli than risk their necks on a downward-hurtling bike.

Conversely, though plenty of mountain bikers stand ready to hurl themselves down any steep, rocky slope in the Lower 48, many are spooked by the idea of travel in rural Mexico.

These are not entirely unfounded fears: The U.S. State Department warned in January of escalating violence among drug traffickers in Mexico’s border areas. Though we’re well south of the most troubled areas, locals will acknowledge (if you leave their names out) that many Batopilas residents, in the absence of other options, make their living by cultivating marijuana in the canyon.

So, to make this two-wheeled plunge, it’s not surprising that most bikers, like Kloet, come with an organized group.

An uphill battle won

I catch a ride with Kloet’s travel mates in a creeping van as the Atlanta cyclist grinds upward. At one point, they holler at the sight of a lone figure in his telltale green biking jersey, looking defeated on the roadside ahead.

But it’s a false alarm. Drawing closer, we see we’ve confused his green shirt with that of a Tarahumara man. Kloet is farther along, hammering away at those pedals, squeezing thigh muscles, inching past cardon cactus and mesquite.

And then, eventually, the pines. By noon, he’s climbed through the sub-tropics, through the desert, back into the mountains. And he’s bushed.

“Going up around those bends, with all that loose ground, is a lot harder than going down,” Kloet says.

A victor in his condition, I decide, should be allowed to state the obvious.

This isn’t a 100% triumph — the blacktop doesn’t begin for a few more miles. But Kloet got close. In about four hours, he has made about 25 miles, gaining something like 5,000 feet, to the outskirts of a little Tarahumara town called Quirare. Now the air is thin again, and somewhere on the climb, Kloet has picked up a few more scrapes, a bit of trickling blood.

Enough, he decides. Time to dismount and take on water and calories. To be specific: a bottle, a banana and a burrito. Breakfast of Copper Canyon champions.