Rattlesnakes

Say no to uncontrollable bleeding

Source of this article – Los Angeles Times, May 18, 2004.

The Southern Pacific rattlesnake Ralph Prado kept as a pet last year sank its fangs into him and pumped venom into his body for an unheard of 15 seconds. It took multiple blood transfusions and 58 vials of antivenin to save the Yucaipa man’s life, said Dr. Sean Bush, the physician who treated him.

Another victim was not so lucky. The man was bitten during a hike last May in the Lytle Creek area of the San Bernardino Mountains and was treated with 42 vials of antivenin. He writhed uncontrollably, bleeding “everywhere except his brain,” says Bush, before dying days later.

Though these episodes may make for riveting TV, how likely is the possibility of being attacked by a rattlesnake while playing in the great outdoors?

More than 100 people in California are bitten by rattlers each year. Statewide, one or two die in a typical year, according to the California Department of Fish and Game. Eight rattlesnake species call California home; seven of them — including the highly toxic Mojave rattler — dwell in Southern California and can inflict serious, even deadly, injuries. Snakebites usually damage tissue at the bite site, but a Mojave rattler’s bite can affect the nervous system.

As the weather warms, encounters between rattlesnakes and humans increase. Rattlers leave the mountain dens they’ve hibernated in over the winter to feed, says Tim Hovey, a Fish and Game biologist. In dry weather, snakes will venture farther to find water, boosting the chances of them turning up in foothill neighborhoods.

Morning is a rattler’s prime time to catch some sun, usually in the middle of a trail or curled up on a rock. Once it heats up, the snake heads back to its den to rest, so you’re less likely to see one between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m., Hovey says.

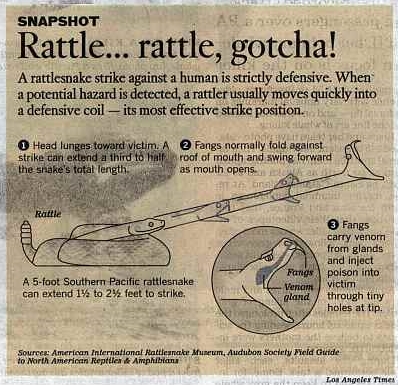

Rodents and small reptiles make up the bulk of a rattlesnake’s diet. Rattlers prefer not to waste venom on humans, says Hovey, but will strike in defense if threatened. They use the rattles on their tails to tell people they mean business.

Baby rattlesnakes have undeveloped rattles called buttons, so their rattle might not be audible. The old camp myth that bites from babies are more dangerous than those from adults is not true, says Bush. Venom toxicity is related to volume, and adults pump out much more venom during a strike, he says. However, there do tend to be more bites from baby rattlers in late summer and fall, he adds, when the young predominate.

The best way to avoid a bite is to watch where you’re going and avoid sticking your hands and feet in places you can’t see. Always step onto a rock or log rather than over it. Hovey advises swinging a walking stick while hiking to warn snakes of your approach. When you encounter a snake, stay back and give it room to retreat, which it often will do.

Hovey recommends wearing ankle-high hiking boots and loose-fitting pants, so that a snake will grab fabric instead of skin if it strikes.

About 50% to 60% of bite victims are males who’ve been drinking and are “messing with a snake,” says Dr. Robert Norris, chief of emergency medicine at Stanford University Medical Center. Many are bitten while trying to pick up a snake.

The pain starts quickly after a bite, says Norris, and swelling spreads along the affected arm or leg. About 25% to 30% of rattlesnake bites are “dry,” in which no venom is injected. If the snake does spew venom, symptoms include tingling around the mouth, nausea and vomiting, weakness, dizziness, sweating and/or chills.

The venom’s toxins destroy red blood cells. If left untreated, a victim can go into shock and die. About one in five survivors of snakebites has permanent injuries, says Bush.

Contrary to past recommendations, you shouldn’t cut, ice or use a tourniquet to treat a rattlesnake bite, experts say. Immobilize the affected limb, keep the victim calm and get to a hospital as quickly as possible, Bush says. Most experts dismiss snakebite kits designed to extract venom from a bite as useless items that may do more damage than good. “The best things in the wild for a bite are a cellphone and helicopter,” says Bush.

If the bite is severe enough, victims are usually given antivenin. There is currently no shortage of antivenin, as there was two years ago, says Norris, but it’s early in the season.

Treatment is expensive — about $900 a vial for the antivenin CroFab, which is derived from sheep and less likely to cause allergic reactions than an earlier version. The typical charge for treating a single bite can reach $20,000.

Rattlesnakes are a serious threat, so be cautious and show respect when entering their turf. And remember, they do have their good points, like keeping rodent populations in check. “I tell people when they encounter one to take a few steps back and just watch it. It’s a beautiful animal,” says Hovey.